Matricide

by Lucy Sussex

There is an afterlife …

And it appears to be an international airport terminal. How strangely suitable, she thinks, given the time I spent in such places. Charles de Gaulle, Heathrow, LAX she knows, but this terminal is not so immediately familiar. It is typical, though: computer screens, garish carpet, travelers crowding the departure lounges. Departing for where? she wonders. Some other terminal, some afterlife Paris, Athens, Rome?

An announcement comes over the loudspeaker in a string of translated languages. She catches in each the word Changi. Singapore, she thinks. They named it after a prison … again appropriate. No heaven, she thinks, but hell—I've felt that often enough, stumbling jet-lagged off a plane—or even purgatory? She stares at the fellow travelers, but they seem just like any tired passenger encountered in life. Young girls in high fashion, older women in tracksuits, parents pushing strollers, little children running across the carpet. Suddenly she glimpses a woman oddly familiar, seen through the glass of a departure waiting room: middle-sized, between youth and middle age, thin, hair cut conveniently but modishly short, her clothes chic, but comfortable for traveling. Then she realizes the woman is not seen through the glass but darkly reflected in it.

How I used to be, she thinks, with a pang of pleased vanity. Well, better that than the wreck of what I am now. Or the vomitbucket of a few months ago. She moves on, becoming aware that she is not so much stepping as gliding across the concourse. Ghosts walk, she recalls, the thought summoning the memory of a television program, chilling when seen in childhood. Involuntarily she glances down to see her feet, clad in modish, all-purpose (from city walking to boardroom) boots, which are firmly planted on the black plastic of a conveyer belt.

She relaxes and lets the belt transport her past the departure lounges, into the gift-shop section. At the end of the belt she steps off, into walls of duty-free Hermès, cigars, Scotch whisky. Then she stops. Behind one glass shop window is a woman, familiar, older, also stylishly but comfortably dressed. And, she notices, just on the legal edge of air travel, to judge from the bulge beneath her Pregnancy Survival Kit black frock.

As it is the afterlife, she can do now what she wouldn't in real life, satisfy an inappropriate curiosity.

"Excuse me?"

The woman looks up from a display of little Chinese dolls.

"Excuse me, but you were the judge …"

She thinks: Judge Judy I called her at the time; it was Judge Judith something.

Judge Judy gazes at her, head slightly on one side, as if sorting through a mental card file.

"I was the defendant in a case you presided over. In New York. I was sued: Tenenbaum v. Lester. I'm Lester, Sylvie Lester."

"Oh, yes," says the judge. "The case over that ridiculous doll. The hallucination in wax. It made me feel ill just to look at it." She frowns faintly, remembering. "I was only just pregnant at the time."

"You threw the case out. I was so glad, I wanted to thank you."

"No thanks necessary."

"And to say I'm sorry about you and the baby …"

"Sorry?"

That faint frown has returned to Judge Judy's face.

Now I've put my foot in it, Sylvie thinks, but nonetheless can't stop the words.

"Sorry, because you're both dead … like I am; otherwise we wouldn't be here."

"Don't be ridiculous," says the judge. She gestures at the passing passengers, singling out a group of depressed-looking Middle Eastern men. "Do you think that's Mohammed Atta and his merry men? And, just disembarking, the planeloads of their victims?"

"No, it doesn't exactly look like him."

"Of course it isn't. I'm very much alive, and so is my child. So are you, Ms. Lester, for the moment. What happens next is up to you; it always is. We can't pick our beginnings"—with a downward glance—"but we should try and control our endings. Life's that way. And now excuse me, I have to buy a present."

And with a wave of her hand, Sylvie is dismissed, out of the judge's sight, out of the gift shop, out of the airport concourse. She curls up fetally, eyes closed in a personal darkness. We can't control our beginnings, she quotes to herself, but we can control our endings. Yet where in the Sylvie-story do I begin? It'd make a novel in full, and somehow I don't think I've got enough time. Choose scenes, fast backward. Pause.

Maybe it begins with Miles …

Immediately she has the sense of wind in her hair, the indefinable scent of imminent, looming snow, overlaid with coffee and Gauloises. She uncurls into a Paris side street, the outdoor settings of a café, coffee and frites on the table in front of them. She looks up, smiles despite her jet lag.

"At last!" he says, lifting his coffee cup. Miles, a big, amiable bear of a man she'd met in a language course. He was polishing his French before his move to Paris: to my dream life, he had said. Why she was doing the course, she couldn't recall. But they'd gotten on, found a common ground in the arts, their conversation, even in French, a pleasant exchange. They had parted with a kiss on both cheeks, French-style, an invitation: "If you're in Paris, get in touch."

With an implication, a possible double meaning, double entendre.

On the flight from Singapore she hadn't slept well; she could just fall into bed at this point. But whose? That point remains to be negotiated. Miles met her at Charles de Gaulle, took her into town, deposited her bags at the hotel. It's her first time in Paris and despite her tiredness, the boulevards, the rows of Baron Hauptmann's terraces, the style of the Ile de France fascinates. They've spent the morning wandering around, seeing sights, Miles's Paris.

"What is your dream life?"

He answers unhesitatingly. "A studio apartment in a building so full of history the similes fail me. Writing my books. Being a consultant on various art and museum projects, even a film. Just being here."

"I can see why."

He nods, staring back into her face. And so the day passes. Without a word being spoken, just the pressure of her gloved hand on the woollen sleeve of his greatcoat, after dinner they go back not to her hotel but to his apartment. If a pass has been made, she has caught it. And so she falls into his bed, to sleep profoundly, the bulk of his body keeping a chaste distance, on that night at least.

As her head hits his feather pillow in its cool linen cover, the images of Paris slowly fade. They are replaced by something closer in time, something painful: a doctor's surgery in Brooklyn. A vial of yellow liquid, as yellow as the good French wine she drank with Miles, sits on the table. Beside it, a sensor slowly turns a lurid pink.

"It was just a one-night stand," she says.

Or rather a succession of one-night stands, every time I flew into Paris … To the studio apartment, a small space, monastic in its simplicity, the furnishings of good quality, from china to towels, but austere and plain. Everything is functional, no thing extraneous or frivolous. And this from an expert on the beaux arts! She intuits it is a reaction to the collections and collectors he associates with on a daily basis, other people's frippery …

"Maybe. But my dream life is stripped down to essentials," was all he said. "Paris is an expensive place."

She compares her succession of rooms in share houses, her flats here and there, full of mess, valuable or otherwise. Working for Sotheby's, then as a freelance, setting up her own business, meant she was forever discovering arty bits and pieces imminently about to appreciate in value or that she just had to have. Riots of fabrics, and rugs, paintings and photos, cushions and objets d'art, pouffes and feathers, bric-a-brac and unalloyed kitsch. Completely unlike the decor chez Miles. There is no place for her here, she thinks, except as a brief visitor, a one night's guest.

"A one-night stand," she repeats firmly.

The Brooklyn doctor very slightly purses her lips. In answer Sylvie feels first a twinge, then a rush, of nausea. She turns away from that scene, into the blackness behind her eyelids again. No, she thinks, I'm going too fast, slow down.

She opens her eyes, to see the terminal again. A man clears his throat behind her."You're Sylvie Lester?"

In answer she reaches for her card carrier, of antique jet, and withdraws the card. Sylvie Lester, Dealer and Location Service, Antiques, Fine Arts and Collectables.

"Then you're my date."

He looks—there is no other way of saying this—like some sort of Samoan Goth. Dark crinkly hair, a mid-Pacific face offset by small round shades, black as night, that resemble eyeholes in a skull. The clothes are very expensive but worn like a Thunderbird puppet's. They don't fit, and neither does he, in this life or any other.

"Mr. Ween," she recalls.

"Call me D.C. Remember I wanted to buy you a drink, as a grateful client?"

"You're trying to kill me," she says.

He stares at her, impassive. "Not just yet. This is the only time we met, remember, outside the Internet."

Behind him the terminal swirls in her vision, changes slightly, imperceptibly, the colorful plaques of tourist advertisements now showing images of Jazz Festivals, Mardi Gras, the voices around them suddenly dripping Southern U.S. honey.

"This is Baton Rouge," she said. "Or New Orleans. And I'd been asked to give a speech at some antique collector's fair."

"Of which I could only make one afternoon. So I said, let's meet at the airport."

He leads the way through the crowd, people eddying as if preferring not to touch or be near him, to a elevator doorway.

"The VIP lounge. I'm a member."

"Of course."

They disembark at the top floor of the terminal, a big, gilded room looking over the expanse of tarmac, the planes taxiing, circling, landing, regular as some clockwork toy. He chooses a window table, and they sit against a backdrop of metallic, stormbringing sky. As a waitress takes drinks orders, flakes of snow blow past outside, some briefly attaching themselves to the glass before an ephemeral melting. This isn't Baton Rouge, she thinks. Not exactly. But what or where it is, I don't know.

Two margaritas arrive, and, as she sips, he gestures sideways with his head.

"See the guy over there, the corner table?"

She follows his gaze, sees a mop of graying hair, thick glasses, a vaguely familiar face.

"That's Stephen King. My man, my kind of dude."

"He looks like a college professor," she says. A brutal one. Well, that's what they have to be these days to survive, that's what Miles said … At the thought the scene wavers and dims slightly, as if something is trying to return her to Paris and Miles. No, not so fast, she tells herself. You want to be back there, that's obvious, but don't rush. Otherwise you'll miss something important.

"A great man," D.C. continues. "To reach into the world's psyche and extract a can of worms, bring out what scares folks most and rub it in their faces."

He's a good client; she's not about to tell him he's mixing his metaphors.

"I'm more intrigued by his sheer grip on narrative," she says. "To keep on reading, when it's four A.M. on some red-eye shuttle and you're totally grossed out. That's ability."

"I still say it's the scary stuff that makes him powerful. Guess we'll have to agree to differ." He sips from the margarita glass, spraying salt. "Hey, what scares you?"

The way the question is asked, the sly sneaking out of left field, does something to her it shouldn't, brings back a memory so compelling she can't confess it, especially to a stranger and client. She had been nine or ten, impressionable. Idly she had been watching a television program, a fifteen-minute filler before the news. The topic was famous ghosts, and this week's episode was a historic haunted hall in England. It had burnt down, and witnesses saw two figures walking out of the flames. The commentator said: "One had the form of a young woman, the other was a shapeless thing."

The memory still made her want to shudder, at what the "shapeless thing" might have been. It was suggestive of so much, once you let your imagination play with it, as children will: like pulling a scab off a wound, horrified, hurting, but unable to stop.

"You tell me what scares you first," she counters.

"I could … but I won't."

The creepiness she first perceived as an affectation in her client now seems genuine, in much the same way as does Stephen King. If it really is Stephen King, she thinks. Isn't he a reformed alcoholic, not seen in bars at all? As if reading her thoughts, Ween lifts his glass in the direction of the novelist—and for a moment it seems that King lifts his glass of Coke in response, a returned salute.

"A very powerful dude. You ever hear about the guy in the car who ran into King when he was jogging? Near killed him. And guess what, he's dead now. You can't tell me that's an accident, anything less than a revenge. There are dark forces out there, just ready for payback, for an injury to the guy who let them walk free among us."

His tone is admiring, and now she has had quite enough of this weird exchange. "You should be writing horror yourself." She drains the dregs of the margarita, stands. "And now I have a plane to catch."

Without looking up, he says: "You haven't, not here …"

And as she turns to go, he adds, a faint, parting shot: "Unless the plane catches you."

She steps out of the VIP lounge, aware as she does that there is some commotion behind her, people craning, staring out the windows. She walks on, not wanting to look back, not at Ween and his implied threat. Outside she looks for the elevator. She finds it but merely opens the door on a very plush Ladies, marble-topped tables, hibiscus in the vases, gilt-rimmed mirrors …

In which she sees herself as she was a few months ago: hair lifeless, skin white and crepey, even green in tinge. At the sight, the nausea rises again, and she rushes for the nearest receptacle, luckily not the flower vase, but—unhygenically—the basin.

As she holds onto the taps, washing away the regurgitated margarita, somebody comes into the room behind her. She looks up into the mirror and sees her Brooklyn doctor.

"I know they call it morning sickness, but this is morning, noon, and night sickness!"

"It goes with the territory sometimes," the doctor says. "Pregnancy hormones, being overproduced. Unpleasant, but nothing to worry about, unless …"

She walks up behind Sylvie, takes the skirt of her pleated Miyake pullover dress (asymmetric, no crush, go anywhere), and pulls it tight. Revealed is a bulge, not the extent of Judge Judy's, but more than just stomach flab, girly jelly-belly.

"Elsewhere I'm thin," Sylvie says helplessly. "And I used to be thin there too."

"When did you last have your period?"

"I told you, I don't notice such things, but I definitely last had intercourse two months ago. On the fourteenth of July, the French holiday."

"And before that?"

I will not say "I only have sex in Paris," she decides. "Um, March."

The doctor releases the skirt, runs her hand over the bulge clinically, a noncaress.

"You look more than two months. Either you're hopeless with dates, or it's a multiple birth …"

At that Sylvie dry-retches into the basin.

"Or …" The doctor trails into silence, releasing her.

"Sorry," Sylvie mutters to the porcelain.

"It goes with the territory. But Ms. Lester, I'm sending you off for a scan, an ultrasound. If it is more than one fetus, then you need to think hard about your options. You told me you hadn't decided what to do yet."

"I have now." Of all things, it was the memory of a Paris shop, the delectable, tiny bébé things displayed in the window, suddenly now terribly covetable, in all their frills and lace, unexpectedly necessary. If that's a reason, she thinks, it's a bad one. But it is a deciding reason nonetheless.

"I'll take that as a yes?"

Sylvie nods, the motion setting off the nausea again.

"It's hard enough with one, on your own. Can't the father help?"

"Him?" She laughs without humor. "He's got a perfect life."

"Wife?"

"No, life. No room in it for a child."

Or me, being around all the time, she thinks. She starts to cry, and the bathroom blurs around her. In the time it takes to collect herself, wipe the tears away, she finds herself no longer in the bathroom but the elevator. The doors open at the ground floor, and she steps into … chaos. People are running down the concourse, their screaming near drowned out by the wails of fire engines. Speeding toward the terminal is a taxiing plane, too fast to stop. She stares at the narrow window where a pilot should be but sees nothing, a void. The plane screeches across tarmac, its nose cone hitting the glass of an observation window, shattering it.

And then, for that brief moment, time is slowed. She sees the glass shatter, and through the gap comes cold wind and eddies of snowfall. I could run, she thinks, save myself … if I want to.

The plane slams into the terminal in a shower of glass and snow, the wheels rucking up carpet and demolishing the departure lounge chairs. The wings strike the side of the terminal, and they concertina, breaking off in chunks.

It's like my body, she thinks, a plane wreck, hit by a plane, hit by Miles, even if unintentionally. Still her feet in their smart boots remain planted on the floor as if she has no flight reflex, no sense of fear.

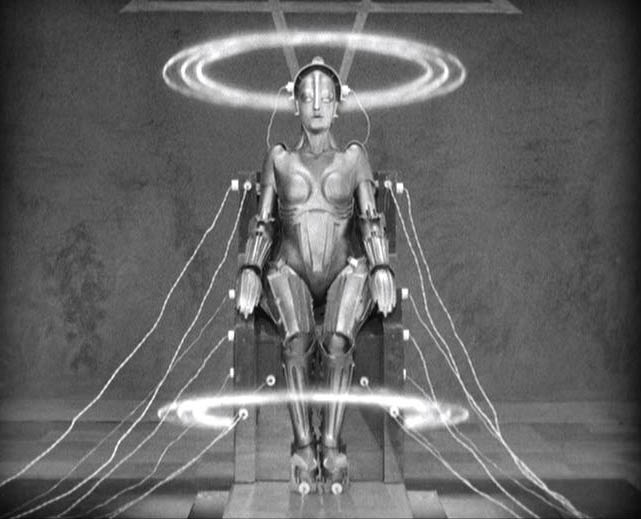

The plane bursts into flame. And in the center of that fire, as she smells the acrid gasoline-plastic smell, coughs at the billowing black smoke, she sees something she recognizes: an ovoid shape, grotesque and pretty, like a hallucination in wax.

That is where it really begins, she thinks. It all started with that doll, when my life started to go pear-shaped. The day I went to Miles's, as usual, after a flight from Bali. I unpacked my suitcases there and then on his polished wood floor to show off the weird and wonderful things I had found for my clients. And as I sat there, bubble wrap and dirty washing strewn around me, the thought struck me that every time I saw him I got more fond of him, his accepting my dropping in with minimal notice, uncomplaining as I temporarily took over his life. And I liked his laugh so much, his concocting divine meals from things he just happened to have in his fridge, like mini zucchini and goat cheese, his being the perfect gentleman, particularly in the bedroom …

But did he like me because I wasn't there all the time?

"I have something for you," he says. "Or for one of your clients. Though I can't imagine who would want it."

She pauses in her unpacking. "But Miles, you don't collect; you say you haven't the space."

"I don't. But as I was passing through a flea market, in a town where I'd stopped to buy Doyenne du Comice, the queen of pears, I saw this little doyenne, weird though she is."

He hands her a cardboard box tied with string, which she unties like a child at a birthday party. Underneath is a layer of aromatic wood shavings, which she lifts to reveal a monstrosity. An egg made of papier-mâché, with breaking through the shell the limbs and head of, not a chick, but a baby doll.

"I think it must have been some Easter gift," he says.

The cracks in the shell are realistically etched; the doll's chubby limbs are moulded in translucent, flesh-colored wax. Impossibly blue china eyes stare up at her from a wax face surmounted by a tuft of curly blond hair and a lacy bonnet.

"Originally confectionary inside," he says. "The head comes off"—and he demonstrates. Revealed is an empty void, with a fusty, vaguely sickly smell, as if of antique sweetmeats.

"I'm impressed," she says after a moment. "That is really, truly, deeply grotesque."

"I thought you'd say that."

"I had a doll collector on my books, but Kewpie only. And I can't think of anyone else among the clients. Maybe I'll invite bids, like with eBay. I've got an intern back in New York, it'd give her something to do … just put it on the website."

She has a brand-new mobile phone, with digital software, in her luggage. She locates it, positions the doll on Miles's scrubbed wood table, takes a photo. Eat your heart out, Anne Geddes, she thinks, as the image wends its electronic way across the oceans.

Hours later, in bed, the mobile rings.

"Did you have to get Chinese Revolutionary Opera as your ringtone?" Miles murmurs into the pillow.

"The mobile's duty-free; I haven't had time to customize it."

She sits up in bed to talk, in the dark.

"Who was that?" he asks, as she ends the call.

"A Mrs. Lotte Tenenbaum. I think she must have bribed the intern to give her my mobile number."

"The name is horribly familiar. And I mean horribly. Let me waken my brain cells." He switches on the light, slaps his broad brow theatrically. "Oh dear! Sylvie, what obscure collecting universe have you been inhabiting? Mrs. Tenenbaum's famous, indeed notorious in some circles."

"She wants the doll. She says her family used to own it."

"She says that about a lot of things. Her family lost everything in the Holocaust. Including her sanity. She's old, very rich, and trouble. I refuse to sell this doll to her."

"But …"

"I'm the vendor, and I insist on my right to refuse objectionable offers."

She stares at him. "But I practically said yes …"

"I overheard, and you didn't. You had a tone in your voice: well, if she wants to make out on the first date, what will she do afterward? Like the shrewd businesswoman you are. And if she wants it so badly, who else might?"

A silence, broken by the sound of a car in the street below, then the phone again.

"I'll kill that intern," she says. "Or sack her. Whatever comes first."

Again, after the conversation she reports to Miles, the prospective vendor of the merchandise, being businesslike even if stark naked. "That was D. C. Ween."

"What sort of a name is that? Deceased Ween! Like Halloween without the hallow?"

"'What obscure collecting universe have you been inhabiting?'" she echoes. "It's a stage name. You ever hear of D. C. Ween and the All-Hallows Band? You ever hear them? Particularly unlistenable death metal, but sold millions. He's retired now but still reacting against what must have been the fundamentalist upbringing from hell. Very selective, will pay anything for the right stuff, if it's horrific: mortuary memorabilia, mojos, voodoo. He too wants the doll …"

"No doubt to stick pins in it."

"You may not be so wrong there." She thinks uncomfortably of D.C.'s most recent purchase: some handmade voodoo dolls, in a crude wooden boat, found washed up on a Mexican beach.

"Well, he can't have it either. I refuse to let this doll, grotesque though it is, get into the wrong hands."

"You're making things very difficult for me," she sighs.

And what eventuates is their very first row. It arrives in stages, as does their cooling. Each time she'd arrive in Paris, she'd update Miles on the trouble he'd caused her. Never anger a client, that was one of her rules, and Miles had got two clients murderously mad with her, expressed in their own insane ways.

"What's this?" he said.

"Take it. Open it."

He cocks one eyebrow at her but takes the heavy paper envelope, sealed with red wax. The seal is a grinning skull, and, with an expression of distaste, he slips a thumb under the flap, cracking the skull from crown to bony chin.

"It's a hatpin. Nineteenth century, from the look of it. And dirty …"

"The tip is crusted with blood. I had the last one analyzed."

"The last one?"

"It's the latest in a series, sent via FedEx, security express, vampire bat if he could."

He looks obtuse, and she nearly yells at him: "D.C.! It's from D. C. Ween!"

"How childish of him," Miles merely says.

Next time she comes armed with a tape from her answering machine. Not content with losing the law case, Lotte Tenenbaum kept calling, somehow locating the mobile numbers, even when changed, the unlisted New York number.

"It's Yiddish," she says. "And I've had it translated. Read it!"

He reads the transcript, hands it back to her. "'May an umbrella enter your belly and open up!'" That's a classic Yiddish curse. She's said worse to several dealers or curators of my acquaintance."

"Do you have to be so calm and collected all the time?"

"I'm not getting myself flustered about it, if that's what you mean. If you are, then you should go and get an intervention order."

"It's your FAULT!"

"No, it's theirs, for thinking the answer to their personal problems lies in possessions. Even if that is how you make your living."

That does it; her temper bolts away from her, as if running for freedom down the streets and alleys of inner-city Paris. She says things in the heat of the moment, to be remembered and regretted later, like a cold-collation revenge. He gets storm-sullen in response. Slamming the door she goes out for a walk alone, amid the happy French families celebrating the national holiday. She returns in the dark, foot- and heartsore, with the stars out. The apartment is dark, and she can see his hulking silhouette by the open window. Inside, she nears him, pauses. In response he takes her by the hand.

Yet even sorting things out in bed resolves only the physical tension and not the emotional. She hasn't been back to Paris since; she doesn't know what Miles did with the doll, she didn't ask. Maybe he locked it up in some Parisian safe-deposit box.

But now here it is; in the center of the flame, the exploding aircraft, beginning to burn, baby, burn. So this is all about you, she thinks. A doll that two rather strange people want desperately but that everyone else thinks weird. You made Judge Judy feel nauseous, but not me. When I was pregnant I didn't think of you once. Perhaps I should have, because what happened was even more grotesque than you, Easter dolly.

Snow is drifting still into the terminal, despite the fire. It settles on a green-tinged screen beside the table where she lies now, legs drawn up in a technological rape, the scanner coated with gel and inserted, revealing her most secret places.

Where's the baby? she thinks. Instead she says: "That looks like snow."

"It isn't," says the scanner technician, a statuesque black woman. Then: "Honey … I'm really sorry."

"It's not a baby." It's a statement, no question in her voice.

"What you see as snow is called a mole."

"Mole?" A snow mole?

"A hydatidiform mole. It's rare, but it happens. A sperm cell hit an egg that was defective, without a nucleus. You got the symptoms of pregnancy but no fetus."

All she can think to say is: "Why me? Why me?"—as if it were something personal.

"There's risk factors, like being Asian, which you're not, age, nutrition …"

She thinks: I'm not young; I know I don't eat properly, except in Paris.

"… but understand, honey, it's not your fault. You gotta understand that, whatever happens. Because the snow on the scanner is placental cells, developing uncontrollably."

"It sounds like a tumor," she says dully.

"It can be. You need a D&C, dilation and curettage. ASAP."

In pre-op, she finds herself on a production line, women entering in day clothes, then being sent to cubicles, where they changed, to emerge identical in white hospital gowns, white bathrobes that are one size, oversize, paper mob caps on head, paper bootees on their feet. And suddenly she starts to cry, for something she has lost but never really had, no time even to buy pretty French baby clothes, no time to plan, no time to think of a potential now lost. And the crying continues as they lift her onto the hospital trolley, wheel her into the operating theatre. She is nearly hysterical as the anesthetist lifts her hand, strokes it clinically to reveal the vein, pricks her with the poisoned needle.

"Are you still there?" says a nurse.

She clenches her fists, answers through sobs: "Yes, unfortunately."

A nurse strokes her cheek, a professional sympathy. Then blackness. She wakes later in a room full of curtained beds, for a moment forgetful, then with consciousness coming the memory: of waking up the day after an exam failed; of a boyfriend dumping her; of her nonexistent child. And she rips the drip from the back of her hand.

Nurses and later counselors come and talk to her, the sounds of their voices like water over smooth river stones. She coils around her internal void, slowly beginning to shift from depression into anger.

A counselor: "Do you think of the baby as an angel?"

"I most certainly do not!"

She gets discharged; she heads back to her apartment and her lonely art-deco bed. Next morning she gets up, goes to her computer terminal, then the office. The following day she is out of the city, heading across the airways to do what she does best, finding things (and in the process losing herself?). She is back briefly then jets down to the Southern Hemisphere, more searching. At some point an airline clerk offers her a flight through Paris, but she refuses. Would Miles really want me to land on him with the ultimate sob story? she wonders. When a man expresses his tenderness with sex, what happens when that is temporarily forbidden by medical interdict? The nights and days blur across time zones, she knows she eventually stops bleeding but can't pinpoint just when. She just keeps on working, traveling increasingly frantically she realizes …

Until even she has to stop, to come back and find a series of phone messages, urgent demands, this time from her Brooklyn doctor.

"I told you that you were to come back for tests!"

Yes, she did, Sylvie thinks. "You also said complications were rare." But I couldn't stand the thought of coming here, to this surgery with all its implicit reminders. And so I left, not really caring about anything much.

"But not impossible. Well, since you're here, we'll check your beta-HCG."

"That's the pregnancy hormone," she recalls.

"And if it's still there, so is the mole."

"But how?" Hadn't it been removed?

"Metastasized—traveling though your system."

"That sounds like cancer," she says.

"It is."

After the test, the doctor's face says it all.

"Do you have someone to care for you?"

Maybe, she thinks, then shakes her head. If I couldn't even tell Miles I was pregnant, how can I tell him what's happened now?

She closes her eyes again, in sudden fear. Darkness returns behind her eyelids, bringing with it the smell, not of a doctor's office, but an aviation disaster. And I'm a gynecological disaster, she thinks. I thought I had a baby, but I never did; my egg was addled, empty in its core. My child transformed into a monster, and now it's trying to kill me. What's the word, the child killing the mother? Matricide.

She opens her eyes to a stinging reminder: the acrid chemicals smoking out the terminal. Her feet move now, taking one step, then another, toward the burning plane. The doll is at the center of the flame, as if on a stake. It started with you, she thinks. My clients cursing me, and as if they really had power, the worst thing in my life occurred. And I'm still paying for it now, with chemotherapy. My life—such as it is—is measured in hospitals and drugs, my business and my body have gone to hell. Which is where I could go too, just now.

The heat is intense, and the doll is succumbing to it, the lace cap flaming in little points, the mohair wig frizzing, the papier-mâché smoldering, the chubby wax limbs deforming, the pretty face melting, with only the embedded glass eyes keeping their shape. One falls out, revealing darkness. The doll is becoming something shapeless … which seems to advance toward her.

"No!" She reaches through the flames, the pleated polyester of her Miyake smoldering in the heat, and takes hold of what remains of the doll. The hot wax burns but she doesn't let go. Her hands move, cupping, caressing the wax, which almost seems to squirm between her fingers. In her grip the wax loses its formlessness and takes shape: not the doll as was, the weird Easter baby, but a ball. She molds it slightly at both ends, and there she has it: an egg. She presses it to her, the fabrics of her ruined clothes falling away. The wax shape presses into the flesh of her belly. She pushes hard, and slowly it sinks in, the flesh closing and flattening over it. Now it is just an egg, an unfulfilled potential, hidden inside her.

Someone grabs her arm, yells at her. Now she is running, in the grasp of a fireman, as fire trucks converge, fill the terminal with white chemical foam.

He releases her, pointing to a line of waiting ambulances, shouting: "Lady, life's that way!"

She flees through the terminal, now empty except for disaster crews. Well, almost empty: slumped in a departure lounge she finds two figures, side by side: an old, withered woman with bitter, hawklike features, and a man in black, his dark glasses askew to reveal unexpectedly milquetoast eyes. Her former vengeful clients, she realizes.

"I'm sorry," she says. "I'm sorry for what happened to you, Mrs. Tenenbaum. And whatever it was that turned you into an aficionado of evil, D.C. But the universe is like that. Look what it did to me—not even in your most vindictive dreams could you have expected such a revenge. So we're quits."

Neither moves nor responds. Are they dead, overcome by fumes? She suddenly couldn't care in the least. All she sees is the word flashing on the departure screens: Paris. She could just go through those gates, step onto the waiting plane, and within hours be stepping into Miles's little apartment again. She can almost … no, she can see him now, televised on the screen. He sits at his table, a half bottle of wine and the remains of a baguette beside his piles of books and papers. For the first time, she realizes that his perfect life is actually rather lonely.

She reaches into the pocket of her ruined Miyake, brings out her mobile. As she activates it, the same image of Miles appears on its miniature screen. She presses buttons, summoning his oh-so-familiar Paris number. And as she does, the terminal fades. There is just a pool of light around her, night in her New York apartment, where she lies on her art-deco bed, surrounded by medications and her once-prized collectables, a sickly stick of a woman suddenly at the point where she has to ask for help, or else.

She presses the final button, to dial a small apartment in the Rive Gauche. And she waits for Miles to reply.

The End

© 2005 by Lucy Sussex and SCIFI.COM